UX your life.

Applying the user-centered process to your life (and stuff).

The following originally appeared in Smashing Magazine in June 6, 2018. What follows is an iterative update, but the lessons and process herein remain in use.

What does your office look like? This was a Tuesday—a workday!—after my wife and I redesigned our lives and careers and became business partners. (Photo by the author)

Everything is designed, whether we make time for it or not. Our smartphones and TVs, our cars and houses, even our pets and our kids are the products of purposeful creativity.

So why not our lives?

A great many of us are, currently, in a position where we might look at our jobs — or even our relationships — and wonder, “Why have I stayed here so long? Is this really where I want or even need to be. Am I in a position where I can do something about it?”

The simple — and sometimes harsh — the answer is that we don’t often make intentional decisions about our lives and our careers like we do in our work for clients and bosses. Instead, having once made the decision to accept a position or enter a relationship, inertia takes over. We become reactive rather than active participants in our own lives and, like legacy products, are gradually less and less in touch with the choices and the opportunities that put us there in the first place.

Or, in UX terms: We stop doing user research, we stop iterating, and we stop meeting our own needs. And our lives and careers come less usable and enjoyable as a result of this negligence.

Thankfully, all the research, design, and testing tools we need to intentionally design our lives are easily acquired and learned. And you don’t need special training or a trust fund to do it. All you need is the willingness to ask yourself difficult questions and risk change.

You might just end up doing the work you want, having the life-work balance you need, and both of those with the time you need for what’s most important to you.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t admit, the idea of applying UX tools to my life didn’t come quickly. UX design principles are applicable to a much wider range of projects than the discipline typically concerns itself, but it was only through some dramatic personal trials that I was finally compelled to test these methods against my own life and those of my family. That is to say, though, I’m not just an evangelist for these methods, I also use them.

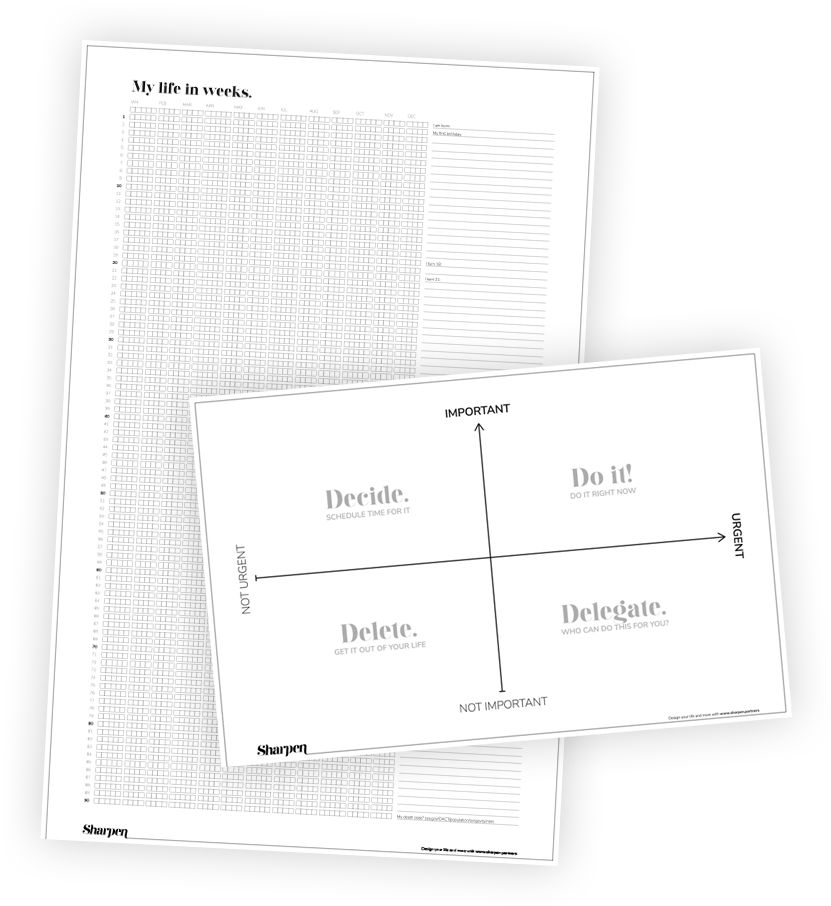

Get started! Follow along with your own Life In Weeks and Eisenhower Matrix.

So how do you UX your life?

In this article, I’ll introduce you to four tools and techniques you can use to get started:

Your Life In Weeks

A current state audit of your past.Eisenhower Matrix

A usability assessment for your present and your priorities.Affinity Mapping

A qualitative method for identifying — and later retrospecting on — your success metrics (KPIs).Prototyping Life

Because you’ve got to try it before you live it.

But first…

Business as usual:

The user-centered design process.

Look familiar? The design process in its simplest form. (Original illustration by Christopher Holm-Hansen, thenounproject.com, modified by the author)

Design thinking and its deliberate creative and experimental process provides an excellent blueprint for how to perform user research on yourself, create the life you need, and test the results.

This user-centered design process is nothing new. In many ways, people have been practicing this iterative process since our ancestors first talked to each other and sketched on cave walls. Call it design thinking, UX, or simply problem-solving — it’s much the same from agency to agency, department to department, regardless of the proprietary frame.

The user-centered design process is, most simply:

Phase 1: Research

The first step to finding any design solution is to talk to users and stakeholders and validate the problem (and not just respond to the reported symptoms). This research is also used to align user and business needs with what’s technically and economically feasible. This first step in the process is tremendously freeing — you don’t need to toil in isolation. Your user knows what they need, and this research will help you infer it.Phase 2: Design

Don’t just make things beautiful — though beauty is joyful! Focus on creating solutions for the specific needs, pain-points, and opportunities your research phase identified. And remember, design is both a noun and a verb. Yes, you deliver designs for your clients, but design is — first and foremost — a process of insight, trial, and error. And once you have a solution in mind…Phase 3: Testing

Test early and test often. When your solutions are still low-fi (before they go to development) and absolutely before they go to market, put them in front of real users to make sure you’re solving the right problems. Become an expert in making mistakes and iterating on the lessons those mistakes teach you. It’s key to producing the best solutions.Repeat

Most design-thinking literature illustrates how the design process is applied to products, software, apps, or web design. At Sharpen, we also apply this process to graphic design, content creation, education, and filmmaking. And it’s for that reason we don’t call it the UX design process. We drop the abbreviated adjective because, in our experience, the process works just as well for presentations and parenting as it does for enterprise software.

The process is about problem-solving. We just have to turn the process on ourselves.

Expanding the scope:

User-centered parenting.

Talk about a pain point. Using UX basics to solve a parenting problem opened the door to a wider application of the process and — mercifully — saved our tender feet.

As creatives and as the parents of five elementary-aged kiddos, one of the first places we tried to apply the design process to our lives was to the problems of parenting.

In our case, the kids didn’t clean up their Legos. Like, ever. And stepping on a Lego might just be the most painful thing that can happen to you in your own home. They’re all right angles, unshatterable plastic, and invariably in places where you otherwise feel safe, like the kitchen or the bathroom.

But how can you research, design, and test a parenting issue — such as getting kids to pick up their Legos — using the user-centered design process?

Research.

For reals. If your product requires me to protect myself against it in my own home, the problem might be the product. (Photo by BRAND STATION/LEGO/Piwee)

We’re far from the first parents to struggle with the painful reality of stepping on little plastic knives. And like most parents, we’d learned threats and consequences were inadequate to the task of changing our kids’ behavior.

So we started with a current-state contextual analysis: The kid’s legos were kept in square canvas boxes in square Ikea bookcases in a room with a carpeted floor. Typically, the kids would pour the Legos out on the carpet — for the benefit of sorting through the small pieces while simultaneously incurring the pain-point that Legos are notoriously hard to clean up off the carpet.

We also did a competitive analysis and were surprised to learn that, back in 2015, Lego appeared to acknowledge this problem and teamed up Brand Station to create some Lego-safe slippers. But, sadly, this was both a limited run and an impractical solution.

All users, great and small. It’s tempting to think users are paying customer or website visitors. But once you widen your perspective, users are everywhere. Even in your own home. (Photo by the author)

Lastly, we conducted user interviews. We knew the stakeholder perspective: We wanted the Legos to stay in their bins or — failing that — for the kids to pick them up after they were played with. But we didn’t assume we knew what the users wanted. So we talked to each of them in turn (no focus groups!) and what we found was eye opening. Of course, the kids didn’t want to pick up their Legos. It was inconvenient for play and difficult because of the carpet. But we were surprised to learn that the kids had also considered the Lego problem — they didn’t like discipline, after all — and they already had a solution in mind. If anything, like good users, they were frustrated we hadn’t asked sooner.

Design.

Repurposing affordances. What works for one interaction often works for another. And with a little creativity and flexibility, some solutions present themselves. (Photos by Ikea and KidKraft)

Remember when I said, your user knows what they need?

One of our users asked us, “What about the train table with the big flat top and the large flat drawer underneath.”

Eureka.

By swapping the contents of the Lego bins with the train table, we solved nearly all stakeholder and user pain points in one change of platform:

Legos of all sizes were easy to find in the broad flat drawer.

The large flat surface of the train table was a better surface for assembling and cleaning up Legos than was the carpet.

Clean up was easy — just roll the drawer closed!

Opportunity bonus: It painlessly let us retire the train toys the kids had already outgrown.

Testing.

No solution is ever perfect, and this was no exception. Despite its simplicity, iteration was quickly necessary. For instance, each kid claimed the entire surface of the top deck. And the lower drawer was rarely pushed in without a reminder.

But you know what? We haven’t stepped on a Lego in years. #TrustTheProcess.

The ultimate experience:

User-centered living.

Knowing how to apply the design process to our professional work, and emboldened from UXing our kids, we began to apply the process to something bigger — perhaps the biggest something of all.

Our lives.

This is not a plan. This is bullsh*t.

The Internet is full of advice on this topic. And it’s easy to confuse its ubiquitous inspirational messages for a path to self-improvement and a mindful life. But I’d argue such messages — effective, perhaps for short-term encouragement — are damaging. Why?

They feature:

Vague phrases or platitudes.

Disingenuous speakers, often without examples.

The implication of attainable or achieved perfection.

Calls for sudden, uninformed optimism.

But most damning, these messages are often too-high-level, include privileged and entitled narratives masquerading as lessons, or present life as a zero-sum pursuit reminiscent of Cortés burning his ships.

In short, they’re bullsh!t.

What we need are practical tools we can learn from and apply to our own experiences. People don’t want to find the thing they’re most passionate about, then do it on nights and weekends for the rest of their lives. They want an intentional life they’re in control of. Full time. And still make rent.

So let’s take deliberate control of our lives using the same tools and techniques we use for client work or for getting the kids to pick up their damn legos.

Content auditing your past:

Your life in weeks.

My life, circa Spring Break. Grey is unstructured time, green is education, and blue is my career (each color in tints to represent changes in schools or employers). White dots represent positive events, black dots represent negative ones. Orange dots are opportunities I can predict. Empty dots are weeks yet lived. (Illustration by the author)

The best way I’ve found to get started designing your life is to take a look back at how you’ve lived your life so far. It’s the ultimate content audit, and it’s one of the most eye-opening acts of introspection you can do.

Tim Urban introduced the concept of looking at your life in weeks on his occasional blog, Wait But Why. It’s a reflective audit of your past reduced to a graph featuring 52 boxes per row, with each box representing a week and each row, a year. And combined with a Social Security Administration death estimate, it presents a total look at the life you’ve lived and the time you have left.

You can get started right now by downloading a Your Life In Weeks template and by following along with my historical audit.

Your Life In Weeks maps the high points and low points in your life. How it’s been spent so far and what lies ahead.

What were the big events in your life?

How have you spent your time so far?

What events can you forecast?

How do you want to spend your time left?

This audit is an analog for quantifiable user and usability research techniques such as website analytics, conversion rates, or behavior surveys. The result is a snapshot of one user’s unique life and career. Yours.

Start by looking back…

Where and when did you go to school?

When did you turn 18, 21, 40?

When did you get your first job? When did your career begin?

When and where were your favorite trips?

When and where did you move?

When were your major career changes or professional events?

What about relationships, weddings, or breakups?

When were your kids born?

And don’t forget major personal events: health issues, traumas, success, or other impactful life changes.

Youth is wasted on the young. I spent the first few years of my life with mostly unstructured time (grey) before attending a variety of schools (shades of green) in North Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, France, and Scotland. I also moved a few times (white circles). Annotations are in the margins. (Illustration by the author)

Adulting is hard. My first summer and salaried jobs led to founding my first company and the inevitable quarter-life crisis. After graduate school, life got more complicated: I closed my company, got divorced, and dealt with a few health crises (black dots) but also had kids, got remarried, and published my first novel (white dots). (Illustration by the author)

What can you look forward to…

Where do you want your career to go and by when?

What are your personal goals?

Got kids? When is your last Spring Break with them? When do they move out?

When might you retire?

Maximize the future. Looking forward, I can forecast four remaining Spring Breaks with all my kids (as a divorcee, they’re with me every other year). I also know when the last summer vacation with all them is and when they’ll start moving out to college. (Illustration by the author)

How full is your progress bar? Social Security Administration helps forecast your death date. But don’t worry. The older you already are, the longer you’ll make it. (Illustration by the author)

The perspective this audit reveals can be humbling but it’s better than keeping your head in the sand. Or in the cubicle. Realizing your 40th really is your midlife might be the incentive you need for real change, knowing your kids will move out in a few years might help you re-prioritize, or seeing how much time you spent working on someone else’s dream might give you the motivation to start working for your own.

When I audited myself, I was shocked by how much time I’d spent at jobs that were poor fits for me. And at how little time I had left to do something else. I was also shocked to see how little time I had left with my kids at home, even as young as they are. Suddenly, the pain of sitting in traffic or spending an evening away at work took on new meaning. I didn’t resent my past — what’s done is done and there’s no way to change it — but I did let it color how I saw my present and my future.

Usability testing the present:

Eisenhower matrix.

Once you’ve looked back at your past, it’s time to look at how you’re spending your present.

An Eisenhower matrix — cleverly named for the US president and general that saved the world — is a simple quadrant graph that juxtaposes urgency (typically, the X-axis) with importance (typically the Y-axis). It helps to identify your priorities to help you focus on using your time well, not just filling it.

Put simply, this tool helps you:

Figure out what’s important to you.

Prioritize it.

Most of us struggle every day (or in even smaller units of time) to figure out the most important thing we need to do right now. We take inventories of what people expect from us, of what we’ve promised to do for others, or of what feels like needs tackling right away. Then we prioritize our schedules around these needs.

What’s important to you? It’s easy to get caught up in urgency — or perceived urgency — and disregard what’s important. But I often find that the most important things aren’t particularly urgent and, therefore, must be consciously prioritized. (Illustration by the author)

Like a feature prioritization exercise for a piece of software, this analytical tool helps separate the must-haves and should-haves from the could- and would-haves. It does this by challenging inertia and assumption — by making us validate the activities that eat up the only commodity we’ll never get more of — time.

You can download a blank Eisenhower matrix and start sorting your present as I take you through my own.

Start by listing everything you do — and everything you wish you were doing — on Post-Its and honestly measure how urgent and important those activities are to you right now. Then take a moment. Look at it. This might be the first time you’ve let yourself acknowledge the fruitless things that keep you busy or the priorities unfulfilled inside you.

WHAT’S IMPORTANT AND URGENT?

Deadlines

Health crises

Legal obligations (e.g., jury duty)

Bills and taxes

Rent or mortgage (if it’s the right time of the month)

WHAT’S IMPORTANT BUT NOT URGENT?

Something you’re passionate about but which doesn’t have a deadline

A long-term project

Family time

Planning

Self-care

WHAT’S URGENT BUT NOT IMPORTANT?

Phone calls

Texts and Slacks

Most emails

Unscheduled favors

Most interruptions

WHAT’S NEITHER IMPORTANT OR URGENT

TV (yes, even Netflix)

Social media

Video games (unless it falls into the self-care category)

Any communication arriving outside pre-defined or appropriate hours (e.g., heads down time, vacations, family time)

The goal is to identify what’s important, not just what’s urgent. To identify your priorities. And as you repeat this activity over the course of weeks or even years, it makes you conscious of how you spend your time and can have a tremendous impact on how well that time is spent. Because the humbling fact is, no one else is going to prioritize what’s important to you. Your loving partner, your supportive family, your boss and your clients — they all have their own priorities. They each have something that’s most important to them. And those priorities don’t necessarily align with yours.

Because the things that are important to each of us — not necessarily urgent — need time in our schedules if they’re going to provide us with genuine and lasting self-actualization. These are our priorities. And you know what you’re supposed to do with priorities.

Prioritize them.

Get sh!t done. “The key is not to prioritize your schedule but to schedule your priorities.” — Stephen Covey, Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. (Illustration by the author)

Identifying what your priorities are is critical to getting them into your schedule. Because, if you want to paint or travel or spend time with the kids or start a business, no one else is going to put that first. You have to. It is up to you to identify what’s important and then find time for it. And if time isn’t found for your priorities, you only have one person to blame.

We do these matrixes regularly, both for family and business planning. And one of the things I often take away from this exercise is the reminder to schedule blocks of time for the kids. And to schedule time for the thing I’m most passionate about — writing. I am a designer who writes but I aspire to become a writer who designs. And I’ll only get there if I prioritize it.

Success metrics for the future:

Affinity mapping.

Great minds think alike. Team affinity mapping can help you and your family, or you and your business partners, align your priorities. My wife and I did this activity when we started our business to make sure we were on the same page. And we’ve looked back at it, regularly, to measure if we’re staying on target. (Photo by the author)

If you’ve ever seen a police procedural, you’ve seen an affinity map.

Affinity maps are a simple way to find patterns in qualitative data. UXers often use them to make sense of user interviews and survey data, to find patterns that inform personae or user requirements, and to tease out that most elusive gap.

In regards to designing your life, an affinity map is a powerful technique for individuals, partners, and teams to determine what they want and need out of their lives, to synthesize that information into actionable and measurable requirements, and to create a vision of what their life might look like in the future.

You don’t need a template to get started affinity mapping. Just a lot of Post-It notes and a nice big wall, window, or table.

How to affinity map your life (alone or with your life/business partners).

Write down any important goal you want to achieve on its own Post-it.

Write down important values or activities you want to prioritize on its own Post-it.

Categorize the insights under “I” statements to keep the analysis from the user’s (your!) point of view.

Organize that data by the insights it suggests. For instance, notes reading “I want to spend more time with my kids” and “I don’t want to commute for an hour each way” might fall under the heading “I want to work close to home.”

Timebox the exercise. You can easily spend all day on this one. Set a timer to make sure you don’t spend it overthinking (technical term: navel gazing).

This is a shockingly quick and easy technique to synthesize the insights from Your Life In Weeks and your Eisenhower matrix. And by framing the results in “I” statements, your aggregate research begins speaking back to you — as a pseudo personae of yourself or of your partnership with others.

Insights such as “I want to work close to home” and “I want to work with important causes” become your life’s requirements and the success metrics (KPIs). They’ll form the basis for testing and retrospectives.

Speaking of testing…

Prototype or dive right in.

Now that you’ve audited, validated, and created a vision for the life you want to live, what do you do with this information?

Design a solution!

Maybe you only need to change one thing. Maybe you need to change everything! Maybe you need to save up some runway money if the change impacts your income or your expenses. Maybe you need to dramatically cut your expenses. No change is without consequence, and your life’s requirements are different from anyone else’s.

When my wife sat down and did these activities, we determined we wanted to:

Work together

Work from home, so we don’t have to commute

Start our work day early, so we’re done by the time the kids come home from school

Not check email or slack after hours or on weekends

Make time for our priorities and our passion projects.

All about the pies. Aligning our priorities helped define the services or business offers and the delicious return on the investment our clients can expect.

Central to this vision of the life we wanted was a new business — one that met the functional and reliability needs of income, insurance, and career while also satisfying the usability and joy requirements of interest, collaboration, and self-actualization. And, in the process, these activities also helped us identify what services that business would offer. Design, content, education, and friendship became the verticals we wanted to give our time to and take fulfillment from.

But we didn’t just jump in, heedless or without regard to the impact a shift in employment and income might have on our family. Instead, we prototyped what this new business might look like before committing it to the market.

Prototyping is serious business. We took advantage of a local hackathon to test working together and with a team before quitting our day jobs. (Photos by the author)

Using after-hours freelance client work and hackathons, we tested various workstyles, teams, and tools while also assessing more abstract but critical business and lifestyle concerns like hourly rates, remote collaboration, and shifted office hours. And with each successive prototype, we:

Observed (research)

Iterated (design)

Retrospected (testing).

Some of the solutions that emerged from this were:

A remote-work team model based on analogue synchronous communication and digital statuses (eg. phone calls and Slack stand-ups).

No dedicated task management system — everyone has their preferred accountability method. My wife and I, for instance, prefer pen and paper lists and talking to each other instead of process automation tools (we learned we reallyhate Trello!).

Our URL — importantshit.co — is a screener to filter clients for personality and humor compatibility.

Google Friday-style passion project time, built into our schedules to help us prioritize what’s important to each of us.

And some of the problems we identified:

We both hate bookkeeping — there’s a lot to learn.

Scaling a remote team requires much more deliberate management.

New business development is hard — we might need to hire someone to help with that.

So when we finally went full time, we already had a sense of what worked for us and what challenges required further learning and iteration. And because we prototyped, first, we had the confidence and a few clients in place so that we didn’t have to save too much money before making the change.

The ROI For designing your life.

Superficially, we designed a new business for ourselves. More deeply, though, we took control of variables and circumstances that let us meet our self-identified lifestyle goals: spending more time with the kids, prioritizing our marriage and our family above work, giving ourselves time to practice and grow our passions, and better control our financial futures.

The return on investment for designing your life is about as straightforward as design solutions get. As Bill Burnett and Dave Evans put it, “A well-designed life is a life that is generative — it is constantly creative, productive, changing, evolving, and there is always the possibility of surprise. You get out of it more than you put in.”

Hopefully you’ll see how a Your Life In Weeks audit can help you learn from your past, how an Eisenhower matrix can help you prioritize the present, and how a simple affinity mapping exercise for your wants and needs can help you see beyond money-based decisions and assess if you’re making the right decisions regarding family, clients, and project.

Live and work, by design. Mindfully designing our lives and our careers allowed us to pursue our own business and our separate passions (elliedecker.com and o-jd.com). (photos by the author and his wife)

It’s always a give and a take. We frequently have to go back to our affinity map results to make sure we’re still on target. Or re-prioritize with an Eisenhower matrix — especially in a challenging week. And, sometimes, the urgent trumps the important. It’s life, after all. But always with the understanding that we are each on the hook when our lives aren’t working out the way we want. And that we have the tools and the insights necessary to fix it.

So schedule a kickoff and set a deadline. You’ve got a new project.

Down for more?

Ready to start designing a more mindful life and career? Here are a couple links to help you get started:

This article began life as a conference presentation at Connect.Tech and a subsequent workshop series. It has also appeared as an article on Smashing Magazine.

Ready to calculate your death date? Not everyone is. But for the brave, try the Social Security Administration’s longevity calculator (spoiler, the older you already are, the better you’ll do).

Bill Burnett and Dave Evans, authors of Designing Your Life, maintain a great blog at designyour.life with articles and advice on how to further create a mindful life.

WaitButWhy created the life in weeks tool and uses it in some additional ways, including mapping the lives of famous creatives.

Art of Manliness has a great breakdown of the Eisenhower matrix.

Many of these ideas began life in a series of talks I gave at General Assembly about How to Get Sh*t Done.

Design your future with Sharpen.

We’re excited to show you how Sharpen’s premier team of creative problem solvers (with their fingers on design thinking, technology, architecture, and more) is the right team to help you. Because we do a lot more than just create beautiful, functional solutions—and that “lot more” informs how we approach every problem.

Contact us for a free remote consultation with our innovation leaders to see how we can help you and your company bring your visions to life and be more innovative than ever.